The multicolored, drug-soaked, psychedelic aesthetic of the mid-1960s has never been more popular, or misunderstood. In March, “Mad Men” time-traveled from the cocktail cool of Mid-Century Modern, circa 1962, to that dope-smoke-filled hothouse known as Pop, circa 1966. And in April, Donovan, whose “Mellow Yellow” was released that same year, was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Not bad for a guy who was singing a song that many people have long assumed was about getting high off dried banana peels. In fact, it may have been about vibrators, which makes it about the “sex,” rather than the “drugs,” in “sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll.”

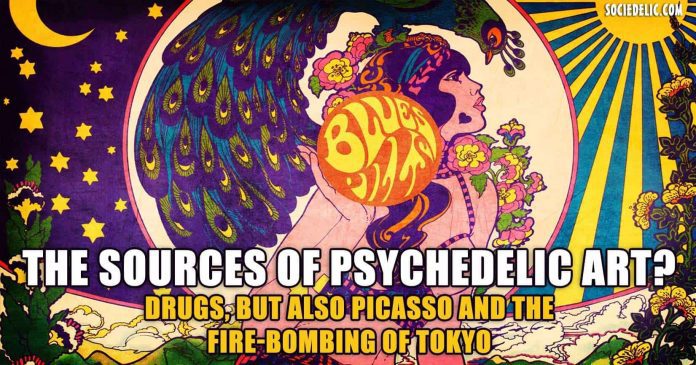

This spring also saw the publication of a new book titled “Electrical Banana: Masters of Psychedelic Art,” by Norman Hathaway and Dan Nadel. Featuring an introductory interview by Hathaway with Paul McCartney, the 208-page paperback shines a bright spotlight on psychedelic artists from Europe, Australia, and Japan, some of whom were never comfortable with the term that came to define them. On Sunday April 29, 2012, the authors and graphic artist Gary Panter will be at MoMA PS1 in New York to talk about the book and show a few film clips provided by some of the artists.

“In the ’60s, I was scorned as a psychedelic artist, especially when seen in the company of Tim Leary.”

Taking its name from a line in Donovan’s famous tune (McCartney played bass on the recording), “Electrical Banana” features interviews with, and artwork by, seven highly influential artists, such as the late Heinz Edelmann, who conceived the landscapes and characters in the animated feature “Yellow Submarine,” even though he describes himself in the book as being “allergic” to many of the most common tropes of psychedelia. Then there’s Tadanori Yokoo, whose collages took their inspiration, in part, anyway, from traditional kimonos. Believe it or not, some of these artists didn’t even take drugs.

“The book originally had about three or four other artists in it,” says Hathaway, “but a couple people kind of fell by the wayside. It wasn’t until later that I noticed that there wasn’t a single American in the book, which I ended up being kind of happy about. Usually when people think of psychedelic art, they primarily think of the Fillmore stuff and not a lot else. It’s always Wes Wilson, Rick Griffin, and Victor Moscoso, but there was a lot going on outside of San Francisco, too.”

The book begins with Heinz Edelmann, a Czech-born graphic designer who was living in Dusseldorf when he got the call to work on “Yellow Submarine,” an animated feature for The Beatles that, much to his chagrin, became his legacy. After all, this was a man who was influenced by artists as diverse as Picasso, Saul Steinberg, and Ben Shahn, and here he was, being asked to draw characters for a film that did not even have a script.

To hear Edelmann tell it, “Yellow Submarine” was a colossally frustrating experience, so much so that he almost didn’t see it through. The breaking point came on one Friday night. “I was full of hate at everybody,” he tells Nadel, “and thought, ‘Well, I’ll resign, but I’m not going out with a whimper, I’ll go out with a bang.’ That is when I did the Meanies, and the Meanies were originally supposed to be Communists. I always wanted the Meanies to win, but I didn’t get my way.”

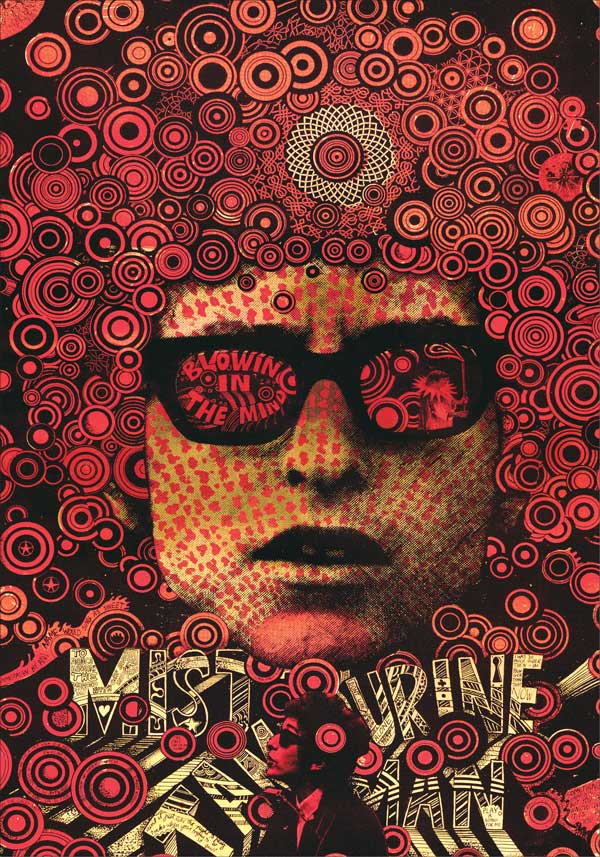

If Edelmann was a reluctant participant in the psychedelic aesthetic (“I don’t like the smell of incense,” he deadpans), the late Australian artist Martin Sharp was an active one, who admired the San Francisco rock-poster artists and cartoonist Robert Crumb in particular. Sharp, who lived in London for a few years before moving back to Australia, even contributed lyrics for “Tales of Brave Ulysses,” which was eventually recorded by Eric Clapton’s band Cream.

“I didn’t know who he was,” Sharp tells Hathaway of his first encounter with Clapton. “I learned Eric was a musician, so I told him I’d just written a song. He replied he’d just written some music. So I wrote the lyrics down for him.” The song appears on Cream’s second album, “Disraeli Gears,” whose 1967 cover was drawn freehand by Sharp at its actual size.

Other artists were more like art directors and the set decorators for the pop-music scene. Dudley Edwards was a member of the London design group Binder, Edwards & Vaughn, which made a business of custom-painting dressers, chairs, and other pieces of furniture, treating them, essentially, like three-dimensional canvases. One of the group’s first non-furniture pieces was a 1960 Buick convertible, which eventually was used by the Kinks on an album cover. That led to a commission for Paul McCartney in 1967.

“I remember I first saw a photo of their painted car in the ‘Sunday Times Magazine’ and thought it was really cool,” recalls McCartney in his interview with Hathaway. “So I got in touch with them and asked the guys if we could have a meeting. We did, and I told them ‘I’ve got a little piano I’d like you to decorate in that same style.’ And at first they were a little bit reluctant to do anything, but I persuaded them. So they measured it all up, took the panel dimensions, and worked up some designs. Then they painted it and did a lovely job. It became my psychedelic piano, which I wrote a lot of songs on, including ‘Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band,’ ‘Fixing A Hole,’ and ‘Hey Jude.’ It’s in its rightful place in my music room in London.”

(Images courtesy Norman Hathaway)

Continue reading Full Article on collectorsweekly.com